MOMENT MAGAZINE

July, 2013

From 1975 to 1979, the Khmer Rouge massacred close to two million Cambodians. An international tribunal is trying the regime's surviving leaders. But powerful forces - poverty, corruption, government revisionism, Buddhist precepts and the passage of time - cloud memory and impede justice.

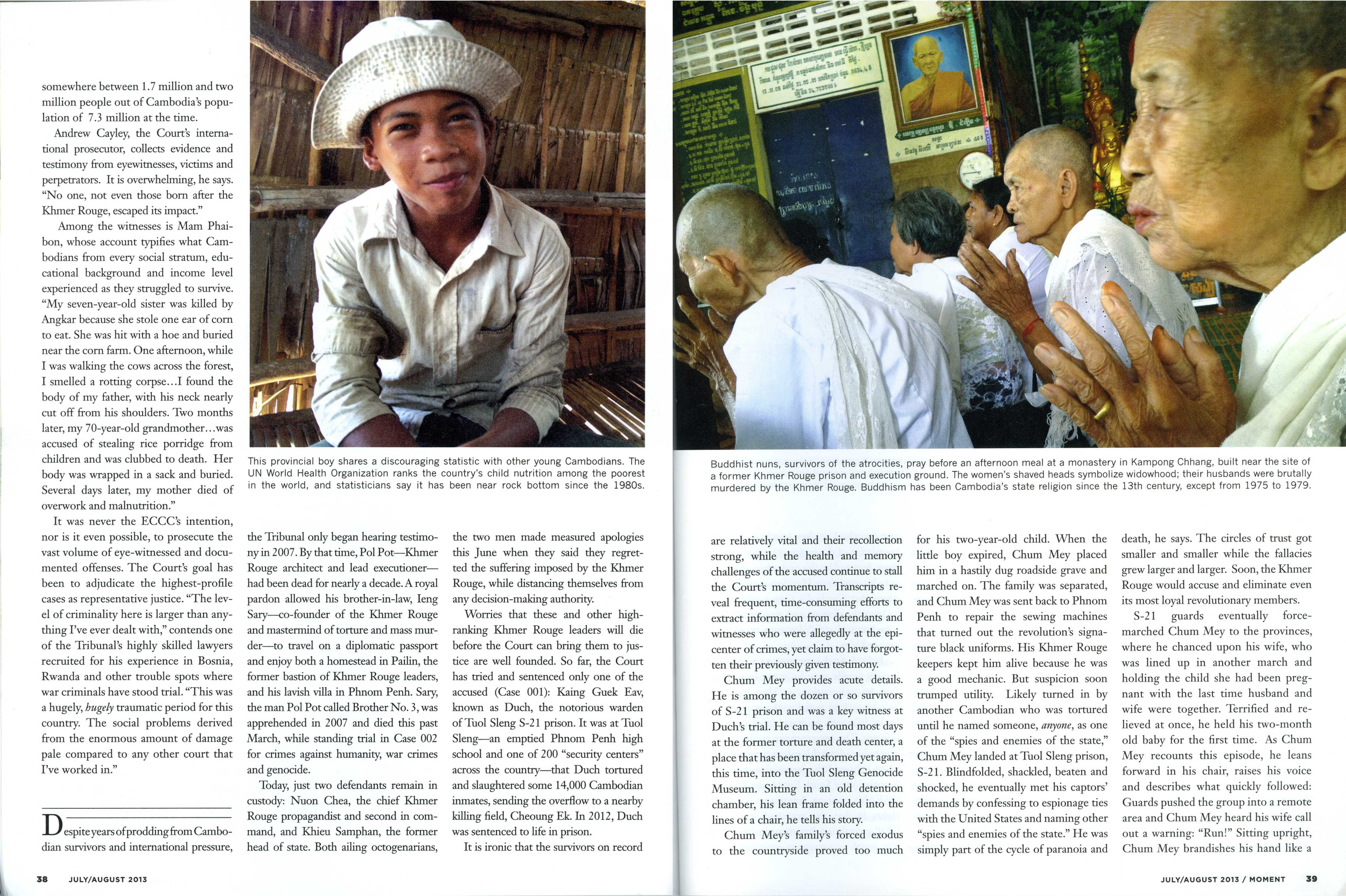

On a steamy morning in a dusty outdoor area 10 miles from Phnom Penh, some 200 Cambodians sit around wood-topped tables under canopies shielding them from a punishing sun. Older women with shaved heads—a symbol of their widowhood—young couples with babies, teenagers and men fill the chain-link fence enclosure. They have come from Cambodia’s outlying provinces for a glimpse of justice inside the pale yellow building complex of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC).

Almost daily, the government transports busloads of people to see this United Nations-backed war tribunal in session. Since the ECCC began its work in 2007, more than 150,000 of Cambodia’s 15 million people have watched the proceedings live. Today’s group waits quietly, patiently, for the doors to open, until they are led single file into the viewing area. Behind a massive protective glass wall, Khmer Rouge founders, strategists and operatives face charges of systematically starving and slaughtering nearly two million of their own citizens during the brutal 1975-1979 Communist regime. Staffed by seven jurists, a bevy of prosecutors, defense lawyers, translators, case investigators and court reporters, this hybrid of local and global jurisprudence slowly sifts through documents and testimony detailing atrocities.

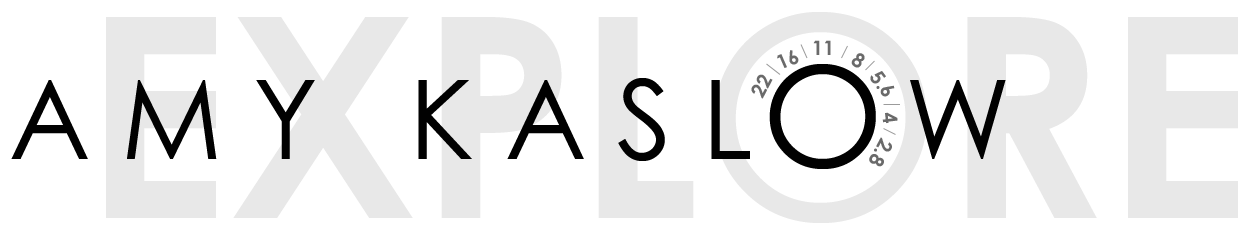

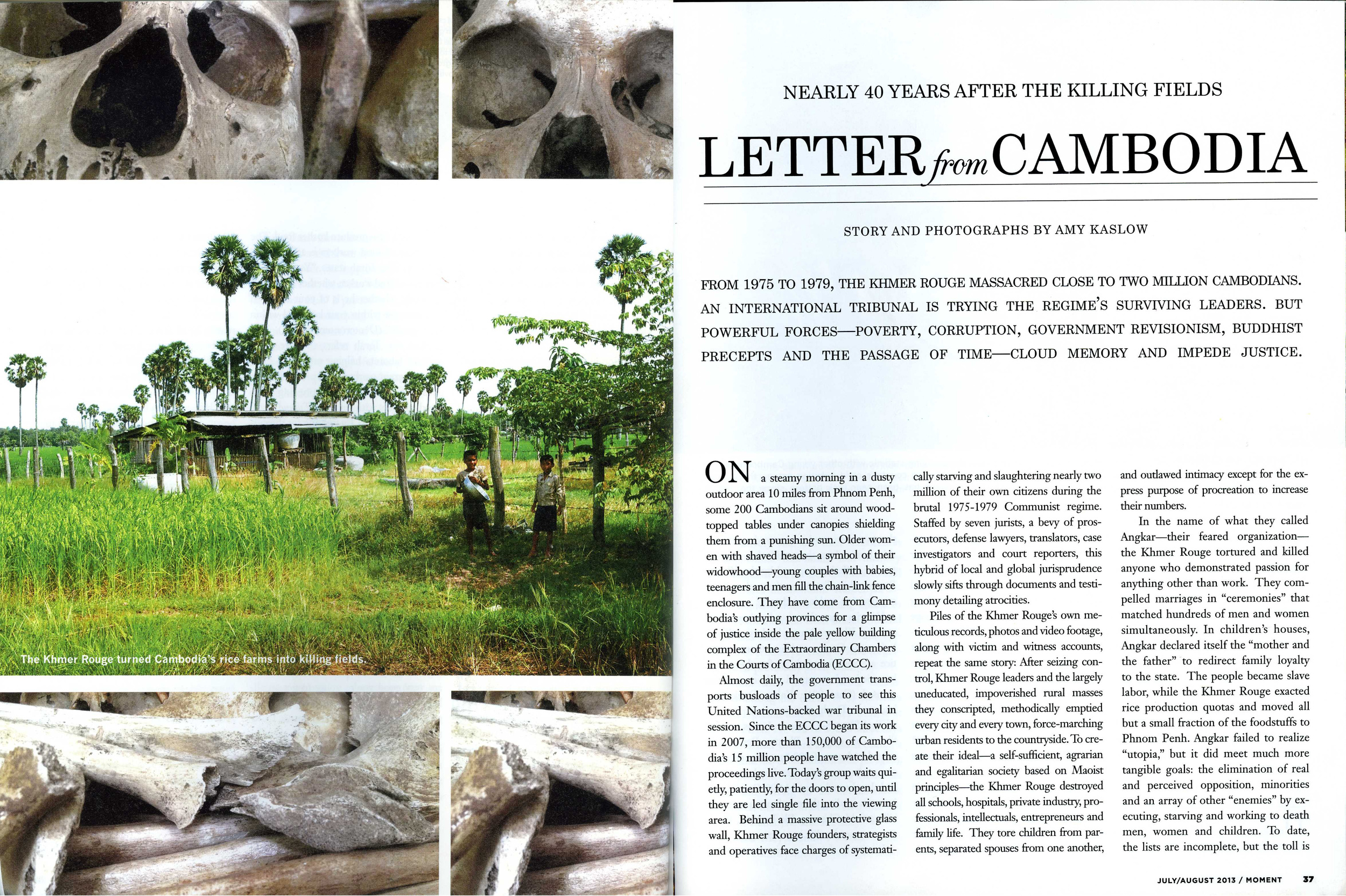

Piles of the Khmer Rouge’s own meticulous records, photos and video footage, along with victim and witness accounts, repeat the same story: After seizing control, Khmer Rouge leaders and the largely uneducated, impoverished rural masses they conscripted, methodically emptied every city and every town, force-marching urban residents to the countryside. To create their ideal—a self-sufficient, agrarian and egalitarian society based on Maoist principles—the Khmer Rouge destroyed all schools, hospitals, private industry, professionals, intellectuals, entrepreneurs and family life. They tore children from parents, separated spouses from one another, and outlawed intimacy except for the express purpose of procreation to increase their numbers.

In the name of what they called Angkar—their feared organization—the Khmer Rouge tortured and killed anyone who demonstrated passion for anything other than work. They compelled marriages in “ceremonies” that matched hundreds of men and women simultaneously. In children’s houses, Angkar declared itself the “mother and the father” to redirect family loyalty to the state. The people became slave labor, while the Khmer Rouge exacted rice production quotas and moved all but a small fraction of the foodstuffs to Phnom Penh. Angkar failed to realize “utopia,” but it did meet much more tangible goals: the elimination of real and perceived opposition, minorities and an array of other “enemies” by executing, starving and working to death men, women and children. To date, the lists are incomplete, but the toll is somewhere between 1.7 million and two million people out of Cambodia’s population of 7.3 million at the time.

Andrew Cayley, the Court’s international prosecutor, collects evidence and testimony from eyewitnesses, victims and perpetrators. It is overwhelming, he says. “No one, not even those born after the Khmer Rouge, escaped its impact.”

Among the witnesses is Mam Phaibon, whose account typifies what Cambodians from every social stratum, educational background and income level experienced as they struggled to survive. “My seven-year-old sister was killed by Angkar because she stole one ear of corn to eat. She was hit with a hoe and buried near the corn farm. One afternoon, while I was walking the cows across the forest, I smelled a rotting corpse…I found the body of my father, with his neck nearly cut off from his shoulders. Two months later, my 70-year-old grandmother…was accused of stealing rice porridge from children and was clubbed to death. Her body was wrapped in a sack and buried. Several days later, my mother died of overwork and malnutrition.”

It was never the ECCC’s intention, nor is it even possible, to prosecute the vast volume of eye-witnessed and documented offenses. The Court’s goal has been to adjudicate the highest-profile cases as representative justice. “The level of criminality here is larger than anything I’ve ever dealt with,” contends one of the Tribunal’s highly skilled lawyers recruited for his experience in Bosnia, Rwanda and other trouble spots where war criminals have stood trial. “This was a hugely, hugely traumatic period for this country. The social problems derived from the enormous amount of damage pale compared to any other court that I’ve worked in.”

Despite years of prodding from Cambodian survivors and international pressure, the Tribunal only began hearing testimony in 2007. By that time, Pol Pot—Khmer Rouge architect and lead executioner—had been dead for nearly a decade. A royal pardon allowed his brother-in-law, Ieng Sary—co-founder of the Khmer Rouge and mastermind of torture and mass murder—to travel on a diplomatic passport and enjoy both a homestead in Pailin, the former bastion of Khmer Rouge leaders, and his lavish villa in Phnom Penh. Sary, the man Pol Pot called Brother No. 3, was apprehended in 2007 and died this past March, while standing trial in Case 002 for crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide. Today, just two defendants remain in custody: Nuon Chea, the chief Khmer Rouge propagandist and second in command, and Khieu Samphan, the former head of state. Both ailing octogenarians, the two men made measured apologies this June when they said they regretted the suffering imposed by the Khmer Rouge, while distancing themselves from any decision-making authority. Worries that these and other high-ranking Khmer Rouge leaders will die before the Court can bring them to justice are well founded. So far, the Court has tried and sentenced only one of the accused (Case 001): Kaing Guek Eav, known as Duch, the notorious warden of Tuol Sleng S-21 prison. It was at Tuol Sleng—an emptied Phnom Penh high school and one of 200 “security centers” across the country—that Duch tortured and slaughtered some 14,000 Cambodian inmates, sending the overflow to a nearby killing field, Choeung Ek. In 2012, Duch was sentenced to life in prison. It is ironic that the survivors on record are relatively vital and their recollection strong, while the health and memory challenges of the accused continue to stall the Court’s momentum. Transcripts reveal frequent, time-consuming efforts to extract information from defendants and witnesses who were allegedly at the epicenter of crimes, yet claim to have forgotten their previously given testimony.

Chum Mey provides acute details. He is among the dozen or so survivors of S-21 prison and was a key witness at Duch’s trial. He can be found most days at the former torture and death center, a place that has been transformed yet again, this time, into the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. Sitting in an old detention chamber, his lean frame folded into the lines of a chair, he tells his story. Chum Mey’s family’s forced exodus to the countryside proved too much for his two-year-old child. When the little boy expired, Chum Mey placed him in a hastily dug roadside grave and marched on. The family was separated, and Chum Mey was sent back to Phnom Penh to repair the sewing machines that turned out the revolution’s signature black uniforms. His Khmer Rouge keepers kept him alive because he was a good mechanic. But suspicion soon trumped utility. Likely turned in by another Cambodian who was tortured until he named someone, anyone, as one of the “spies and enemies of the state,” Chum Mey landed at Tuol Sleng prison, S-21. Blindfolded, shackled, beaten and shocked, he eventually met his captors’ demands by confessing to espionage ties with the United States and naming other “spies and enemies of the state.” He was simply part of the cycle of paranoia and death, he says. The circles of trust got smaller and smaller while the fallacies grew larger and larger. Soon, the Khmer Rouge would accuse and eliminate even its most loyal revolutionary members. S-21 guards eventually force-marched Chum Mey to the provinces, where he chanced upon his wife, who was lined up in another march and holding the child she had been pregnant with the last time husband and wife were together. Terrified and relieved at once, he held his two-month old baby for the first time. As Chum Mey recounts this episode, he leans forward in his chair, raises his voice and describes what quickly followed: Guards pushed the group into a remote area and Chum Mey heard his wife call out a warning: “Run!” Sitting upright, Chum Mey brandishes his hand like a gun, purses his lips and releases a series of staccato “Pop! Pop! Pop!” sounds. The S-21 guards machine-gunned both mother and child; Chum Mey managed to escape. Now in his 80s, he is plagued by an unavoidably vivid image of the murder of his wife and baby. “I cry every night,” he says.

Establishing a tribunal in a country decimated by decades of civil war, where victims and perpetrators have lived side by side from youth to adulthood, has been a study in frustration. Every step of the judicial process has been agonizingly slow, due to “complex political, security and legal reasons” and “the destabilizing social effect of the battered and shocked generation of the war,” says David Scheffer, the UN Secretary-General’s Special Expert on UN Assistance to the Khmer Rouge Trials and who is among the world’s leading legal minds on war crimes.

The Kingdom of Cambodia continues to invoke these reasons as it plays an overactive role in just who is tried and how. Prime Minister Hun Sen, in power for 30 years, first resisted international pressure to set up the Tribunal, and, when it was inevitable, fought hard for a Cambodian-only court. While publicly supporting the Tribunal, he pushes back against prosecuting surviving members of the Khmer Rouge regime, including some who are still in government posts. A recent editorial in The Bangkok Post tagged the ministers of defense, foreign affairs, interior and finance as former Khmer Rouge officers, as well as thousands of government functionaries. Phnom Penh’s support of the Tribunal’s work is a calculated risk: The wider the Court casts its net, the closer it comes to those in positions of power.

At his grand office in the Council of Ministers, an imposing contemporary building along Phnom Penh’s Russian Federation Boulevard, Deputy Prime Minister and Tribunal point-man Sok An sits at the center of a long conference table, flanked by dozens of deputies and aides. The man dubbed “the King of Patronage” by the national press, gives a rambling statement extolling the virtues of the Tribunal and his government’s pivotal role in delivering it to the people. The Court “demonstrate[s] Cambodia’s commitment to the rule of law,” he says. “We have to make our younger generation remember.” As he speaks, his note takers tap away on their iPads, and the authorized television cameramen train their lenses on him.

Despite the government’s positive spin, the Tribunal is a contentious issue in the run-up to Cambodia’s parliamentary elections this July. To deflect attention from his own trial, Tribunal defendant Khieu Samphan has pointed to the prime minister, himself a former Khmer Rouge commander, who Samphan says had extensive knowledge of the regime’s tactics and actions. Angered by this and other challenges to his candidacy, Hun Sen emphatically warns that Cambodia risks a civil war if he loses the election and says he will “respond immediately” if anyone tries to apprehend him.

Indeed, to the government, the Tribunal’s profile may be more important than its prosecution, as Hun Sen and Sok An seek to position the nation as a leader in social, economic and political reforms. The government could hardly wait to broadcast this message regionally, when it hosted the latest nine-member Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) meeting. Among its bragging rights is that the country’s projected GDP growth is 6.7 percent in 2013. But like much government-sanctioned information, official data on hunger, jobs, and wages hardly reflect reality.

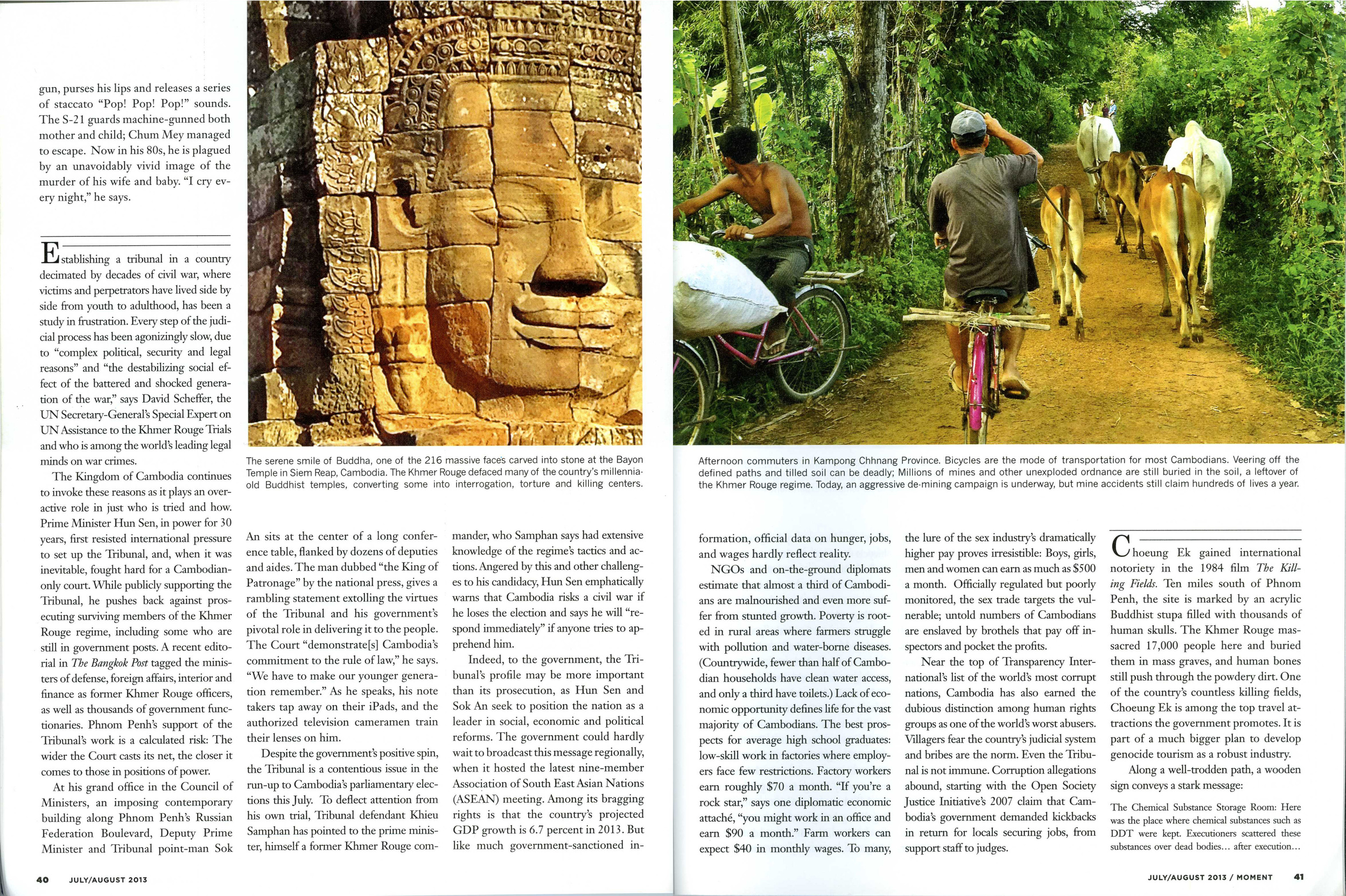

NGOs and on-the-ground diplomats estimate that almost a third of Cambodians are malnourished and even more suffer from stunted growth. Poverty is rooted in rural areas where farmers struggle with pollution and water-borne diseases. (Countrywide, fewer than half of Cambodian households have clean water access, and only a third have toilets.) Lack of economic opportunity defines life for the vast majority of Cambodians. The best prospects for average high school graduates: low-skill work in factories where employers face few restrictions. Factory workers earn roughly $70 a month. “If you’re a rock star,” says one diplomatic economic attaché, “you might work in an office and earn $90 a month.” Farm workers can expect $40 in monthly wages. To many, the lure of the sex industry’s dramatically higher pay proves irresistible: Boys, girls, men and women can earn as much as $500 a month. Officially regulated but poorly monitored, the sex trade targets the vulnerable; untold numbers of Cambodians are enslaved by brothels that pay off inspectors and pocket the profits.

Near the top of Transparency International’s list of the world’s most corrupt nations, Cambodia has also earned the dubious distinction among human rights groups as one of the world’s worst abusers. Villagers fear the country’s judicial system and bribes are the norm. Even the Tribunal is not immune. Corruption allegations abound, starting with the Open Society Justice Initiative’s 2007 claim that Cambodia’s government demanded kickbacks in return for locals securing jobs, from support staff to judges.

Choeung Ek gained international notoriety in the 1984 film The Killing Fields. Ten miles south of Phnom Penh, the site is marked by an acrylic Buddhist stupa filled with thousands of human skulls. The Khmer Rouge massacred 17,000 people here and buried them in mass graves, and human bones still push through the powdery dirt. One of the country’s countless killing fields, Choeung Ek is among the top travel attractions the government promotes. It is part of a much bigger plan to develop genocide tourism as a robust industry.

Along a well-trodden path, a wooden sign conveys a stark message:

“The Chemical Substance Storage Room: Here was the place where chemical substances such as DDT were kept. Executioners scattered these substances over dead bodies… after execution…to eliminate the stench from the dead bodies that could raise suspicion among people working near by the killing fields and… to kill off victims who were buried alive.”

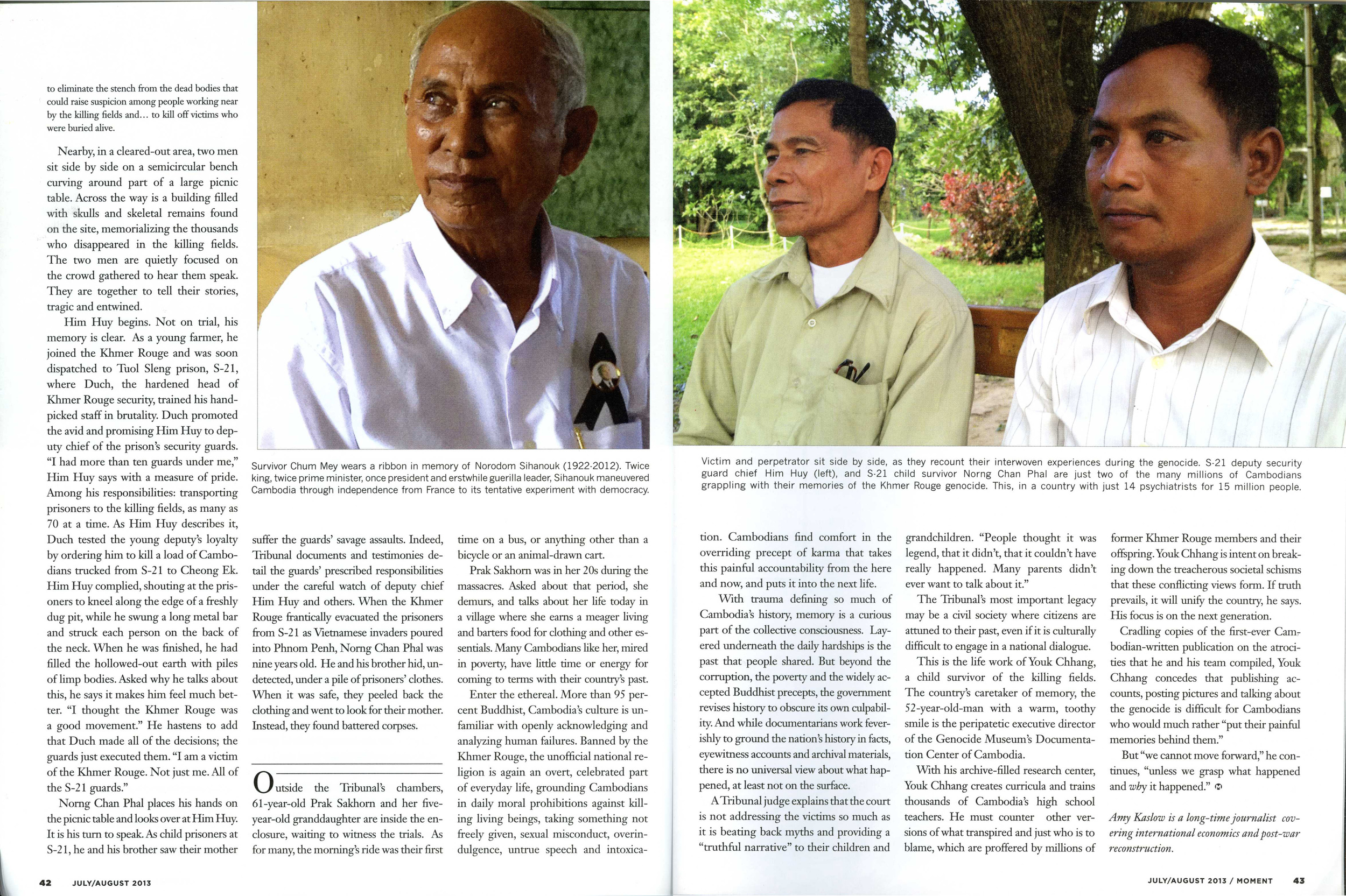

Nearby, in a cleared-out area, two men sit side by side on a semicircular bench curving around part of a large picnic table. Across the way is a building filled with skulls and skeletal remains found on the site, memorializing the thousands who disappeared in the killing fields. The two men are quietly focused on the crowd gathered to hear them speak. They are together to tell their stories, tragic and entwined. Him Huy begins. Not on trial, his memory is clear. As a young farmer, he joined the Khmer Rouge and was soon dispatched to Tuol Sleng prison, S-21, where Duch, the hardened head of Khmer Rouge security, trained his hand-picked staff in brutality. Duch promoted the avid and promising Him Huy to deputy chief of the prison’s security guards. “I had more than ten guards under me,” Him Huy says with a measure of pride. Among his responsibilities: transporting prisoners to the killing fields, as many as 70 at a time. As Him Huy describes it, Duch tested the young deputy’s loyalty by ordering him to kill a load of Cambodians trucked from S-21 to Choeung Ek. Him Huy complied, shouting at the prisoners to kneel along the edge of a freshly dug pit, while he swung a long metal bar and struck each person on the back of the neck. When he was finished, he had filled the hollowed-out earth with piles of limp bodies. Asked why he talks about this, he says it makes him feel much better. “I thought the Khmer Rouge was a good movement.” He hastens to add that Duch made all of the decisions; the guards just executed them. “I am a victim of the Khmer Rouge. Not just me. All of the S-21 guards.” Norng Chan Phal places his hands on the picnic table and looks over at Him Huy. It is his turn to speak. As child prisoners at S-21, he and his brother saw their mother suffer the guards’ savage assaults. Indeed, Tribunal documents and testimonies detail the guards’ prescribed responsibilities under the careful watch of deputy chief Him Huy and others. When the Khmer Rouge frantically evacuated the prisoners from S-21 as Vietnamese invaders poured into Phnom Penh, Norng Chan Phal was nine years old. He and his brother hid, undetected, under a pile of prisoners’ clothes. When it was safe, they peeled back the clothing and went to look for their mother. Instead, they found battered corpses.

Outside the Tribunal’s chambers, 61-year-old Prak Sakhorn and her five-year-old granddaughter are inside the enclosure, waiting to witness the trials. As for many, the morning’s ride was their first time on a bus, or anything other than a bicycle or an animal-drawn cart.

Prak Sakhorn was in her 20s during the massacres. Asked about that period, she demurs, and talks about her life today in a village where she earns a meager living and barters food for clothing and other essentials. Many Cambodians like her, mired in poverty, have little time or energy for coming to terms with their country’s past.

Enter the ethereal. More than 95 percent Buddhist, Cambodia’s culture is unfamiliar with openly acknowledging and analyzing human failures. Banned by the Khmer Rouge, the unofficial national religion is again an overt, celebrated part of everyday life, grounding Cambodians in daily moral prohibitions against killing living beings, taking something not freely given, sexual misconduct, overindulgence, untrue speech and intoxication. Cambodians find comfort in the overriding precept of karma that takes this painful accountability from the here and now, and puts it into the next life.

With trauma defining so much of Cambodia’s history, memory is a curious part of the collective consciousness. Layered underneath the daily hardships is the past that people shared. But beyond the corruption, the poverty and the widely accepted Buddhist precepts, the government revises history to obscure its own culpability. And while documentarians work feverishly to ground the nation’s history in facts, eyewitness accounts and archival materials, there is no universal view about what happened, at least not on the surface.

A Tribunal judge explains that the court is not addressing the victims so much as it is beating back myths and providing a “truthful narrative” to their children and grandchildren. “People thought it was legend, that it didn’t, that it couldn’t have really happened. Many parents didn’t ever want to talk about it.”

The Tribunal’s most important legacy may be a civil society where citizens are attuned to their past, even if it is culturally difficult to engage in a national dialogue.

This is the life work of Youk Chhang, a child survivor of the killing fields. The country’s caretaker of memory, the 52-year-old-man with a warm, toothy smile is the peripatetic executive director of the Genocide Museum’s Documentation Center of Cambodia.

With his archive-filled research center, Youk Chhang creates curricula and trains thousands of Cambodia’s high school teachers. He must counter other versions of what transpired and just who is to blame, which are proffered by millions of former Khmer Rouge members and their offspring. Youk Chhang is intent on breaking down the treacherous societal schisms that these conflicting views form. If truth prevails, it will unify the country, he says. His focus is on the next generation.

Cradling copies of the first-ever Cambodian-written publication on the atrocities that he and his team compiled, Youk Chhang concedes that publishing accounts, posting pictures and talking about the genocide is difficult for Cambodians who would much rather “put their painful memories behind them.”

But “we cannot move forward,” he continues, “unless we grasp what happened and why it happened.”